I spend a lot of time wandering around the market in Leeds. I go there at least a couple of times a week, mainly at lunchtime as an excuse to get away from my desk and see the city at its best.

I’ve shopped there for a while – getting the right things is a game … fruit and veg is generally a little B-grade (fine if it’s fresh but gnarly, not so fine when it’s already on the turn), meat is better than any supermarket, if you use the right butcher, but use the wrong one and it’s diabolical. Spice Corner is still the best place to buy huge bunches of flat leaved parsley to make you feel properly cheffy.

And then, there’s the fishmongers.

Now, landlocked Leeds has a motorway that stretches right to the East coast at Hull and Grimsby, where most of the local catch lands. Freshness is not a problem, and nor is variety. This time, the stall at the top of the row had a full hand of useful cephalopods – squid, cuttlefish and octopus.

All three of these are interchangeable to some extent, and they share similar characteristics. Squid is done a disservice if it doesn’t become calamari, cuttlefish lends itself to stuffing, but what about octopus?

Part of the reason I buy from the market is to freak out my colleagues with some random weird thing stashed in the office fridge. Live crab and lobster have been my highlight, but octopus is a new one, greeted with exactly the mix of terror and bemusement you might imagine.

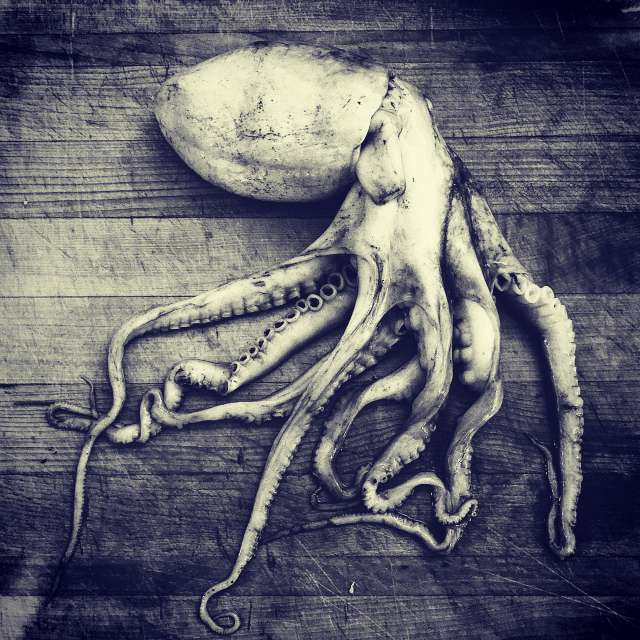

So, here we are. An octopus. Fairly small for an octopus, but recognisably an octopus. Eight arms (note: ‘arms’, not ‘tentacles’), a head, a beak, a sense of superiority borne from the fact that these creatures are apparently some of the most intelligent things alive.

Cooking can be a trial, and one trick I picked up is to freeze the whole thing for a few days before cooking to help to tenderest it. This seemed to work better for me than simply battering it with a rolling-pin, as widely recommended. I think that level of extreme violence may only be necessary for a large specimen with very thick arms.

Preparing the octopus for cooking is relatively straightforward, if messy. There are three parts to bother about – arms, eyes, head.

Start by cutting the tentacles off in one piece just under the eyes, and cut the head off just over the eyes. Discard the eyes and the couple of centimetres of octopus that they’re attached to. Next, remove the beak. This is a hard piece of bone that sits right in the middle of the clump of arms.

Now the messy part. The head is often thrown out, but it’s perfectly edible if prepared properly. Remove all of the gunk and brains by hooking a finger inside the head and pulling it all out. It’s attached in a couple of places, so carefully cut these away with a small knife. There will probably be a lot of ink, so best to do all this over a sink.

With the head relieved of its contents, give it a quick rinse and then peel it. There’s a thin layer of skin on the outside that will pull away once you manage to get hold of a corner. The idea is to end up with a perfectly white and clean sack that looks like a cleaned squid tube.

The last thing to do is to clean the arms. There will be all manner of grit and ink lodged inside the suckers, so flush them out under running water. This is laborious, but necessary, and the occasional action of the suckers is momentarily unnerving. Suckers do suck.

Octopus needs long, slow cooking to tenderise properly, and poaching is the best way to do this. I used a bottle of relatively cheap supermarket Rioja, with a chopped onion, celery sticks, carrots, bay leaves and peppercorns added for flavour. Poaching in red wine changes the colour of the octopus and gives it a deep, earthy flavour, but plain water, perhaps with a squeeze of lemon, would be fine.

To make the arms curl up, bring the poaching liquid up to a low boil, then dunk the arms into the seething mass momentarily, repeating a couple of times. The arms will contract and curl into spirals.

Poach the octopus very gently for anything between forty-five minutes and an hour, depending on size and the thickness of the arms. When it’s done, the flesh will feel tender under the point of a sharp knife.

Octopus prepared in this way can be eaten immediately, sliced, seasoned with salt, pepper and lemon and served with a salad and bread, although it’s excellent left to cool completely before being flashed over a hot griddle pan or barbecue, charring and searing the meat. I have no preference … each method is delicious, and a superb way to prepare this versatile deep sea monster.