So, it’s January, and it’s very, very cold at the moment.

That means that now is the perfect time to cure some meat and hang it out to dry in a shed, outside of a refrigerator, without too much fear of death from botulism.

I exaggerate slightly – botulism is very rare, and basic hygiene prevents it anyway, but there’s definitely something mildly unsettling about eating meat that hasn’t been cooked at all, and more so when it’s been hung up around the house or garden for a good few weeks.

The depths of winter is the perfect time for the more cautious among us to try our hand at curing and air-drying. The air temperature is chilly at best at the moment, so things stay reassuringly cool, especially in a place like a draughty shed or outhouse.

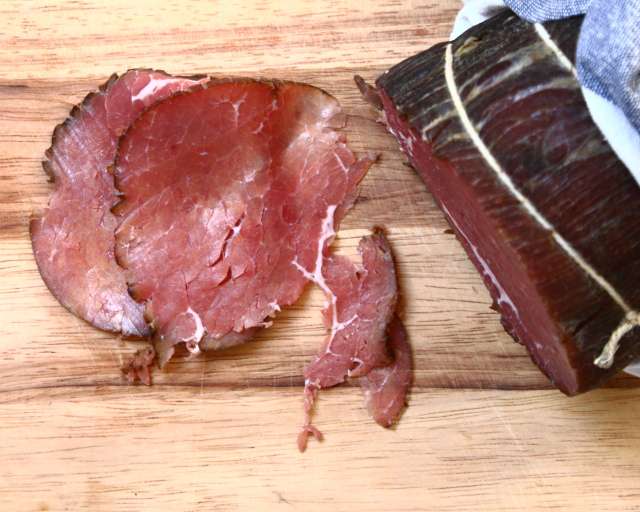

I’ve cured a number of things, but this was one of my most successful experiments. Bresaola is cured silverside of beef, or eye of round in the US and other countries. It’s a dense, hind quarter cut that’s seen a lot of work and is normally suited to slow cooking. It isn’t particularly good when cooked, and the chances are that the cheaper roasting joints you might find at the supermarket will be silverside, but curing it is a different matter.

The curing process is very simple.

Start with a 1.5kg silverside beef joint, a long and fairly thin cut is best, no more than seven or eight centimetres across is best. This allows the cure to work right through the meat.

Cut away every last bit of fat and sinew, including the silverskin that clings to one side, the skin that give the joint its name. Be ruthless with this, taking out everything except the thin layer of fat that runs right through the joint like an artery. There must be no fat remaining.

Next, the cure.

The magic ingredient is Insta Cure , a curing salt that contains nitrates. Nitrates are slow burn, converting to nitrites over many weeks, providing long-lasting protection for the meat. Be very, very careful with Insta Cure , or any other curing salt for that matter – they’re safe used in small quantities, but lethal in large.

Most curing salt is coloured pink to stop it getting mixed up with normal table salt, but the salt I bought wasn’t, so I store it in the original packet, stuffed into an old glass jar, taped shut with gaffer taped, a dire warning on the outside, with the jar stashed in the most inaccessible place in the kitchen, right at the back of the most inconvenient and tallest cupboard.

No child will ever find it, let alone be able to open it.

Of this magic ingredient, you need just 4g, mixed with 25g of salt, 30g of soft brown sugar, 5g of ground black pepper, 6g of chopped rosemary, 6g of thyme leaves and five juniper berries, smashed with the side of a knife.

Place the prepared silverside joint into a suitably sized zip-lock bag and add the cure, massaging it around until all the meat is covered. Put the bag in the fridge and wait a day before turning it over and redistributing the cure. Do this daily for a week.

After seven days of curing, take the joint out of the bag and rinse it well under a running tap, drying it completely in a tea towel.

Use butcher’s knots to tie the joint securely, maybe six or even seven times around, leaving a loop at the top. Wrap the joint in muslin, and tie it safely.

The bresaola is ready to hang now. Choose a cool spot out of direct sunlight and with a steady air circulation. A rickety shed is ideal, or maybe a cool cellar, or even a shady porch. Hang the joint up by the loop – it might be worth installing a small hook to make this easier.

After a week, unwrap the muslin and take a look. The meat will feel harder, tougher, and there might be the start of a white bloom on it, which is perfectly normal. I normally give the meat a quick wipe with a salt water solution and then wrap it back up and leave it to hang again.

Check the bresaola every week for three weeks. After this time, the meat should be ready. It will feel firm, and lighter than when you started.

Inspect the meat carefully for any signs of anything going bad. White mould or blooms are good, anything that smells, or looks yellow, or runny is not. use your judgement and exercise caution.

To serve the bresaola, it’s best to slice it as thinly as possible. Use a meat slicer if you can, or talk your butcher into slicing it for you. My butcher was quite taken with the idea that I was going to cure one of his joints and agreed straight away to slice the finished article in exchange for a sample. If you can’t do this, use a sharp carving knife and go as thin as you can.

Bresaola is one of the easier cuts to cure. Beef is quite a safe meat anyway, one that can be eaten completely raw in any event, and keeping the muscle whole and curing the lot is much more straightforward and less prone to disaster than curing a salami, for example, where the meat has been chopped together. It’s a good place to start, a good place to learn something of the techniques involved in meat curing and preserving, and the results are very good indeed.

Michael Ruhlman’s Charcuterie is a very good introduction to curing, and it’s from there that this method comes.